Argus II Retinal Prosthesis System

As Ophthalmologists, we do everything we can to prevent vision loss, but sometimes there is nothing more we can do. From the invention of braille to bionic retinas, we are continuously finding new ways to help those with low vision. The goal for assistive technology is to improve their functional independence. Here are five of the most impactful and promising innovations in visual assistive technology today.

1. Digital Media and Accessibility tools

Eye Pal Optical Character Recognition Software

Our access to information exploded when we entered the digital age, which has revolutionized the way those with low vision learn and stay up to date. Our computers, tablets, kindles, and phones can not only magnify text, but also read out loud (see: iOS voiceover, Android talkback and even brailleback).

The National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped produces audio books and also provides a free digital player to those registered with the Library for the Blind and Physically Handicapped.

Other membership or paid services include Bookshare, Learning Ally, or Audible (which also has a large selection of free content). There are also special reading apps with communities of individuals who regularly release audio content such as newspapers or podcasts. Finally, optical character recognition products (such as Eye-Pal, Kurzweill 1000, or OpenBook) use cameras to "scan" and convert print to a readable digital form.

(Read more about accessible reading technology).

2. Navigation technology

Smartphones are ubiquitous in our world, and many developers have started making GPS apps that are more "blindness aware." Three popular ones are Nearby Explorer, The Seeing Eye GPS App, and Blindsquare. In addition to giving directions, these apps can regularly announce your location, alert you when you're approaching intersections, and display nearby points of interest.

On a smaller scale, Cheiko Asakawa at Carnegie Mellon has been developing software that can map buildings and campuses using "beacons." They plan to integrate their Navcog app with facial recognition software that can identify acquaintances and recognize facial expressions.

Traveling by car is also no longer an obstacle. With the prevalence of ride sharing services (Uber, Lyft), we can have others drive us. And soon, we can have our cars drive themselves. (See Google's self driving cars)

3. Braille Technology

The search for the "Holy Braille"

Since its invention by Louis Braille in the 19th century, Braille remains an essential form of communication in the low vision community. While originally an entirely analog system, technology has helped maintain Braille's relevance in the modern era.

Both braille writers and readers are now able to connect via bluetooth to smartphones, computers, and tablets. Users can write braille with "braillers" which are essentially braille typewriters.

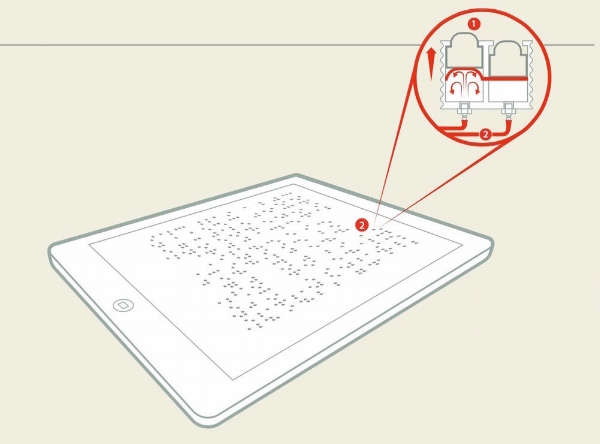

To read, electronic braille displays analyze text line by line, converting them into braille using lines of movable metal or plastic pins. Unfortunately these displays historically have been very expensive, which has limited their adoption.

A new ambitious project on the way, "Holy Braille" hopes to combat this by creating a low cost, full-page refreshable braille display (a braille kindle.) It's currently being developed at the University of Michigan.

4. The Smartcane

The two most common types of canes used by those with low vision are the support cane, which provides physical support, and the probing cane, which probes for obstacles in the path of travel. The probing cane has a long tip that slides along the ground and can identify curbs, stairs, and large obstacles on the ground. However, it often misses hanging bars, signs, and things not fixated on the ground.

The Smartcane is a electronic travel aid that can be attached to the traditional white cane. It uses ultrasound to detect obstacles and converts them to vibrations that the user can feel. Many canes, gloves, etc.. use similar technology, but the SmartCane is the most widely used due to its simplicity and low cost ($50).

5. Retinal prostheses (BIONIC EYES!!)

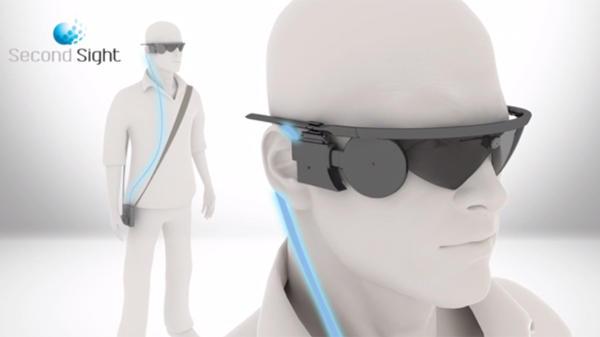

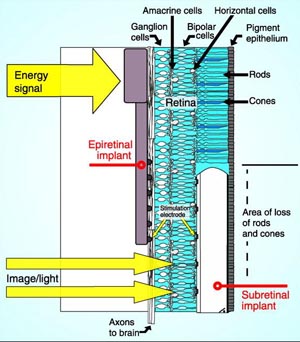

The Argus II is an epiretinal implant. The Implant AG is a subretinal implant.

Science fiction has longed dreamed of cyborgs and "bionic eye." The Argus II and the Retina Implant AG are the two only retinal implants that are currently available to the public outside of clinical trials.

The Argus II system is designed for patients suffering from retinitis pigmentosa. It costs about 150K and involves attaching an implant to the surface of the retina that links to an external digital camera. In one study, 26 of 27 subjects showed a significant improvement on a high contrast visual performance test.

The Retina Implant AG is different than the Argus, as it is implanted below the retina. Developed in Germany over the last 20 years, this implant functions similar to a photoreceptor array and transmits to residual bipolar and horizontal cells in those suffering from AMD or retinitis pigmentosa. It doesn't use a camera, as the implant itself is a complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) camera like chip. It does, however, require a cochlear implant that powers it through induction. Awesome.

FINAL THOUGHTS

These are just a few of the many innovations in the field of accessible technology. You can find a comprehensive database of products on the American Foundation for the Blind website.

I hope this post has been both a practical and informative glance at some of the current and upcoming technologies that exist. I really enjoyed researching this topic, and it has made me very optimistic about the future!

-Louie